Does having coeliac disease affect a woman’s fertility? The scientific research on coeliac disease and fertility is quite inconsistent. Some studies report that coeliac disease can cause infertility and have an unfavourable impact on pregnancy outcomes, but other studies say that coeliac disease does not markedly affect these things.1-8 And of course, the impact of coeliac disease on women’s fertility may be affected by when they’re diagnosed, how long they’ve been eating a gluten-free diet, and how compliant they are with that diet.

We set out to examine the experiences of women with coeliac disease in New Zealand, to see if and how their fertility had been affected by coeliac disease.

We conducted the survey in November 2016. Invitations were sent out by Coeliac New Zealand via their email newsletters and Facebook page. Everyone who responded went into the draw to win a $20 gift card of their choice.

We had 260 responses to the survey. We decided to limit the analysis only to women who had biopsy-proven coeliac disease, just in case the results were skewed by people who had non-coeliac gluten sensitivity. This meant that we analysed responses from 200 women. Our respondents were diagnosed with coeliac disease at an average age of 33 years, but the age at diagnosis ranged from 2 to 80 years old.

We asked respondents to indicate if they had had, or tried to have, a baby before they were diagnosed with coeliac disease. Sixty-five people had been diagnosed before trying to have a baby, and 133 people were diagnosed after starting or trying to start their family. Two people did not answer this question.

The 133 women who had tried to become, or became, pregnant before they were diagnosed with coeliac disease reported an average of two pregnancies before their diagnosis (range: 0 to 14), and an average of 12 months between when they started trying to get pregnant and when they became pregnant for the first time (range: 0 to 132 months). For people who were diagnosed with coeliac disease before trying to start a family, the average delay between starting to try to have a baby and becoming pregnant was only 8 months (range: 0 to 96 months).

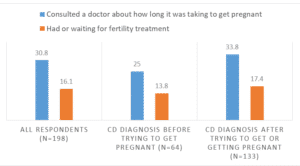

Overall, 61 of our respondents (30.8%) had consulted a doctor about how long it was taking them to get pregnant, and 32 (16.1%) had undergone, or were on the waiting list for, fertility treatment. The likelihood of consulting a doctor about fertility problems was higher in people who were diagnosed with coeliac disease after trying to start a family than in those who were diagnosed before trying to have a baby (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Percentage of respondents who had seen a doctor because of how long it was taking to get pregnant.

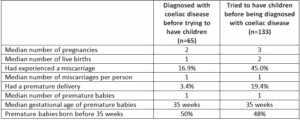

The women in our survey reported up to 14 pregnancies each, with an average of 3 pregnancies per person. Seventy women (35.5%) reported having ever had a miscarriage, but miscarriages were more common in the group who were diagnosed with coeliac disease after trying to start a family (Table 1). The rate of miscarriage in the general population is about one in 4 (25%), which is a little lower than the overall rate in our survey, and definitely lower than the rate we saw in women who were diagnosed with coeliac disease after trying to start a family (45%).

In our survey, 9 out of 10 miscarriages occurred in the first trimester, and this is the time when most miscarriages occur, so there was nothing unusual about this finding. The average number of miscarriages reported by our survey respondents was one per person, and there was no difference between groups based on when they were diagnosed with coeliac disease.

Our survey respondents reported an average of two births per person, and there was no meaningful difference in the number of births between women who already had a coeliac disease diagnosis and those who had not been diagnosed when they started their families.

Overall, 16.5% of the respondents said that they had had a premature baby. This is higher than the New Zealand average of 7.3%.9 The proportion of women who reported a premature delivery was higher in the group who had not been diagnosed with coeliac disease before trying to have children than in those who had a coeliac disease diagnosis already (Table 1). However, in both groups (and in the overall population of respondents), the premature babies arrived at an average of 35 weeks of gestation. Approximately half of the premature babies arrived before week 35 of pregnancy in both groups.

Table 1. Pregnancy and birth results in women who were diagnosed with coeliac disease before and after trying to start a family.

(A word of caution)These findings have not yet been analysed statistically, and have not undergone any independent scientific review. As a form of research, surveys have a few problems. No control group: The best scientific research has a control group for comparison. In this case, we don’t know whether the rates of fertility or pregnancy problems in women with coeliac disease are different from the rates in women without coeliac disease because we didn’t have a control group. Selection bias: People are more likely to respond to surveys if they think they have something interesting to share. So women who think their fertility has been affected by coeliac disease are more likely to have responded to our survey than women who think their fertility is unaffected. This is called selection bias and it has the potential to skew the results towards showing that coeliac disease does affect fertility. Recall bias: The accuracy of survey results depends on how well people remember the events they are being asked about. This is probably less of a problem in our survey, because getting your first period, becoming pregnant or having a miscarriage are quite significant life events, so people are likely to remember them pretty accurately, compared with asking questions about something more mundane like shopping habits. |

Although survey research is not very scientific, the experiences of New Zealand women with coeliac disease are consistent with what some scientific research has shown – that fertility can be affected by undiagnosed coeliac disease. If you know you have coeliac disease and you are eating a gluten-free diet, then you can expect that your chances of getting pregnant, staying pregnant and having a healthy baby are the same as other New Zealand women without coeliac disease.

On the other hand, having difficulty getting pregnant, having recurrent miscarriages, having a baby prematurely, or having babies who are small for their gestational age may be signs of undiagnosed coeliac disease. Some of the women in our survey had been pregnant before and after their coeliac disease diagnosis, and reported having small and early babies before their diagnosis, but bigger babies closer to term after their diagnosis.

Based on what the scientific research has shown, we would recommend that doctors and lead maternity carers screen for coeliac disease in women with:

| Thank you to the team at Coeliac New Zealand, especially Jean, for their assistance in the development and dissemination of this survey, and to everyone who responded to the survey and shared their experiences. Some of the responses told stories of real heartache, and to these people we offer our sincere condolences, as well as admiration for your resilience and hope for happier times ahead. To the seven women who were pregnant when they responded, we wish you safe deliveries and healthy babies. |

As with most things about coeliac disease, there is a lot of variation in people’s experiences, but the best way to enjoy a normal life (including normal fertility) is to stick to a gluten-free diet and a healthy lifestyle.

Catherine Rees is a science writer and lifelong coeliac. She lives in Auckland. She has had one miscarriage and two healthy babies (now teenagers).